PROJECT

Project Description

Linking Hearts is a transnational implementation research project between Canada and China. The project was developed in response to the observed mental health needs of university students in Jinan, Shandong, China. The aims of Linking Hearts are to document the implementation processes and evaluate the effectiveness of an evidence-based intervention, Acceptance and Commitment to Empowerment – Linking Youth and ‘Xin’ (hearts) (ACE-LYNX) to :

(1) decrease stigma of mental illness (attitude);

(2) increase mental health literacy (knowledge);

(3) promote student mental well-being (outcomes); and

(4) build collective capacity to promote mental health of university students (action)

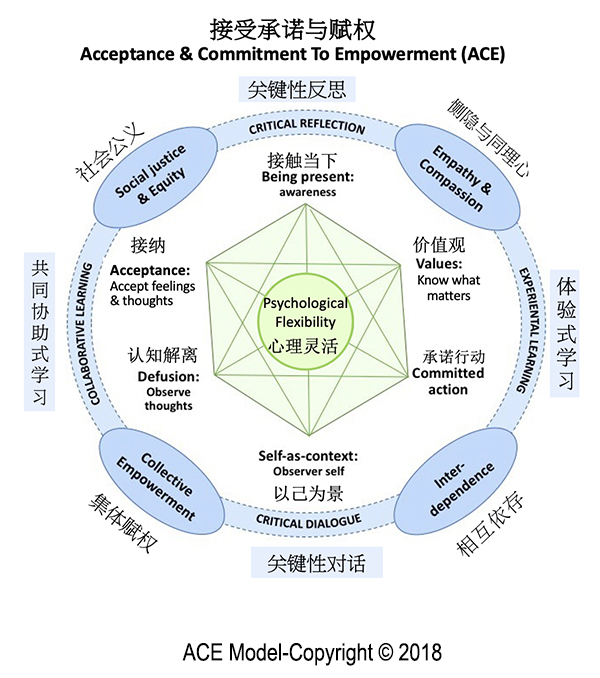

The ACE-LYNX model consists of two integrated components: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral intervention, and Group Empowerment Psychoeducation (GEP), collaborative learning underpinned by the principles of equity, empowerment, and social justice. The project is implemented by through a partnership between the Canadian (CA) team and the Chinese (CN) teams, working collaboratively in three clusters: Data Collection and Analysis (DCA) Cluster; Implementation (IMP) Cluster, and Integrated Knowledge Translation (iKT) Cluster.

Project Aims

Linking Hearts is a transnational implementation research project. The overarching goal of this project is to evaluate and document the process of intervention implementation and resultant knowledge uptake to transform existing health and social service professional capital into expanded capacity in mental health care for university students in China.

The specific aims of the project are to study the adaptation and implementation of an integrated evidence-informed mental health intervention, Acceptance and Commitment to Empowerment – Linking Youth and ‘Xin’ (hearts) (ACE-LYNX), to: (a) improve access to quality mental health care for university students in Jinan, Shandong Province, China; (b) reduce stigma against mental illness that impedes help-seeking, targeted prevention, early identification, timely treatment, and optimal recovery; (c) improve interdisciplinary collaboration through collective empowerment and capacity building; and (d) advance implementation science knowledge in the field of community mental health and in scaling up evidence-informed interventions in transnational and real-life contexts.

Project Background

In China, rapid industrialization and economic growth have led to tremendous stress on individuals living in large cities.1 Epidemiological data indicated a prevalence of 17.5% of all mental disorders, 6.1% of mood disorders, and 5.6% of anxiety disorders. 1 Further, recent data suggested that mental disorders accounted for 9.5% of all disability-adjusted life-years and 23.6% of all years lived with disability in China, which translate into a loss of gross national product at CNY2,681 billion.2

Young people constitute a particularly vulnerable population for the onset of major mental illness, including mood and anxiety disorders as well as psychosis.3 The prevalence of depression and anxiety among children and youth (13-26) in China ranges from 16% to 24%.3 Further, the prevalence of depression among university students is even higher at 20 to 30%,4,5 which is alarming given that one in five of the world’s college/university students are in China.6 Academic pressure, achievement expectations, study stress, living away from home, and ineffective coping strategies were found to be associated with mental distress and psychological disorders, including suicide ideation, self-abuse, internet addiction, anxiety and depression.5,7,8 Targeted prevention, early identification, and intervention are critical in light of increasing evidence on the association between the duration of untreated mental disorders and negative clinical outcomes.9

At the same time, China’s mental health care systems are faced with numerous complex challenges that impede effective and responsive mental health (MH) promotion, prevention, and care. Evidence shows that 91.8% of individuals diagnosed with mental disorder in China never sought mental health care.2 Stigma and low mental health literacy are known barriers to help[1]seeking.10 Mental health literacy refers to people’s “ability to recognize specific disorders; knowing how to seek mental health information; knowledge of risk factors and causes, of self-treatments, and of professional help available; and attitudes that promote recognition and appropriate help seeking.”11 Research shows that lay people in China, regardless of education levels, have limited understanding of mental disorders and often assign causes of mental illness to individual personality traits and social skills.12 Mental health services, largely provided at specialized hospitals, are overstretched. There is a shortage of trained mental health professionals and the current mental health services do not meet the population’s growing needs.2 One study found that 78% of the university health services are managed by student affair offices responsible for civil education and that mental health education is often marginalized.13

Latest Updates on Progress

Youth Mental Health Summit: Local and Global Connections and Perspectives

Collaborating for Success

Adaptation and Integration

Reference:

1 Chen, J., Chen, S., & Landry, P. F. (2015). Urbanization and mental health in China: Linking the 2010 population census with a cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(8), 9012-9024. doi:10.3390/ijerph120809012

2 Liu, J., Yan, F., Ma, X., Guo, H. L., Tang, Y. L., Rakofsky, J. J., . . . Xu, Q. Y. (2016). Perceptions of public attitudes towards persons with mental illness in Beijing, china: Results from a representative survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(3), 443-453.

3 Jin, Y., He, L., Kang, Y., Chen, Y., Lu, W., Ren, X., . . . Yao, Y. (2014). Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety status among students aged 13-26 years. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 7(11), 4420.

4 Lei, X., Xiao, L., Liu, Y., & Li, Y. (2016). Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 11(4), e0153454.

5 Jiang, C. X., Li, Z. Z., Chen, P., & Chen, L. Z. (2015). Prevalence of depression among college-goers in Mainland China: A methodical evaluation and meta- analysis. Medicine, 94(50), e2071

6 China has the world largest university student population. (2016 April 08). China Daily. Accessed March 7, 2016 available at http://mt.sohu.com/20160408/n443680863.shtml

7 Chen, H., Wong, Y., Ran, M., & Gilson, C. (2009). Stress among Shanghai university students: The need for social work support. Journal of Social Work, 9(3), 323-344.

8 Yu, Y., Yang, X., Yang, Y., Chen, L., Qiu, X., Qiao, Z., . . . Bai, B. (2015). The role of family environment in depressive symptoms among university students: A large sample survey in China: E0143612. PLoS One, 10(12) doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143612

9 Ghio, L., Gotelli, S., Marcenaro, M., Amore, M., & Natta, W. (2014). Duration of untreated illness and outcomes in unipolar depression: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152-154, 45-51. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.002

10 Bonabi, H., Müller, M., Ajdacic-Gross, V., Eisele, J., Rodgers, S., Seifritz, E., . . . Rüsch, N. (2016). Mental health literacy, attitudes to help seeking, and perceived need as predictors of mental health service use: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(4), 321-324. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000488

11 Jorm, A. F., Christensen, H., & Griffiths, K. M. (2006). The public’s ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about treatment: Changes in australia over 8 years. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(1), 36-41. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01738.x

12 Gong, A. T., & Furnham, A. (2014). Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders in mainland China: Mental health literacy in China. PsyCh Journal,3(2),144-158. doi:10.1002/pchj.55

13 Yang, W., Lin, L., Zhu, W., & Liang, S. (2015). An introduction to mental health services at universities in China. Mental Health & Prevention, 3(1-2), 11-16. doi:10.1016/j.mhp.2015.04.001